Marine Corps Engineer Memorial Dedicated at National Museum of the Marine Corps

Peter J. Marcucci

Feature Contributor

Photos courtesy of William Stone and Tile

“It’s not often that you see a man’s eyes tear-up—it’s unheard of in a Marine. Yet on May 14, 2014 this rare sight was visible as a group of Marine Corps Engineers gathered at Semper Fidelis Memorial Park on the grounds of the National Museum of The Marine Corps, a 135 acre site adjacent to Marine Corps Base in Quantico.” Remarked Penche Jonnalagadda, Co-owner, of William Stone and Tile of Hubert, North Carolina.

“It’s not often that you see a man’s eyes tear-up—it’s unheard of in a Marine. Yet on May 14, 2014 this rare sight was visible as a group of Marine Corps Engineers gathered at Semper Fidelis Memorial Park on the grounds of the National Museum of The Marine Corps, a 135 acre site adjacent to Marine Corps Base in Quantico.” Remarked Penche Jonnalagadda, Co-owner, of William Stone and Tile of Hubert, North Carolina.

On the overcast day of May 14, 2014, in recognition of the honor, courage and commitment of past and present Marine Corps Engineers, a long-overdue ceremony was held to honor their own.

The observance began inside the Semper Fidelis Memorial Chapel. Attending were several distinguished Marine notables as well as 160 current and former Marines, their families and their guests, who listened as several Marines spoke about the important role of Marine Corps Engineers—especially combat engineers. The splendid and stirring ceremony continued as a representative selection of Marine Corps Engineers veterans who had bravely served in the Afghanistan War, Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Desert Storm, the Vietnam War, the Korean War and World War II recalled memories of these campaigns, and reflected on what it meant to be a Marine and Marine Engineer. Then, after speeches and a robust, enthusiastic rendition of the Marines’ Hymn by the audience, all in attendance were led by a bagpiper down a winding path lined with monuments to stand in front of the new monument, where he played Amazing Grace. Afterwards, the audience sang the National Anthem, followed by a prayer, short speeches, and recognition of the artists involved in producing the monument. The rite concluded with placement of a wreath. All in attendance then gathered for celebration, pictures and to congratulate William Stanton Cucksee, the creator of the monument and Co-Owner of William Stone and Tile.

The observance began inside the Semper Fidelis Memorial Chapel. Attending were several distinguished Marine notables as well as 160 current and former Marines, their families and their guests, who listened as several Marines spoke about the important role of Marine Corps Engineers—especially combat engineers. The splendid and stirring ceremony continued as a representative selection of Marine Corps Engineers veterans who had bravely served in the Afghanistan War, Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Desert Storm, the Vietnam War, the Korean War and World War II recalled memories of these campaigns, and reflected on what it meant to be a Marine and Marine Engineer. Then, after speeches and a robust, enthusiastic rendition of the Marines’ Hymn by the audience, all in attendance were led by a bagpiper down a winding path lined with monuments to stand in front of the new monument, where he played Amazing Grace. Afterwards, the audience sang the National Anthem, followed by a prayer, short speeches, and recognition of the artists involved in producing the monument. The rite concluded with placement of a wreath. All in attendance then gathered for celebration, pictures and to congratulate William Stanton Cucksee, the creator of the monument and Co-Owner of William Stone and Tile.

“It was a honor for me to be selected to build this permanent monument. It wasn’t just a job—it was personal,” said Stan Cucksee.

“It was a honor for me to be selected to build this permanent monument. It wasn’t just a job—it was personal,” said Stan Cucksee.

“When you think about how many Marines that have died, and all the Marines that are dying or still in the service as engineers and what this meant to all of those men, there was no way I was going to disappoint them. My primary purpose was to collaborate with the association and to give them what they wanted.”

The Marine Corps Engineer Association (MCEA) was established in 1991 to promote and perpetuate current and retired Marine Corps engineers and additionally to sponsor and promote an accurate record of their achievements. Fundraising was carried out over a four-year period and was sponsored by the generous donations of caring individuals and organizations, including the Society of American Military Engineers.

The Marine Corps Engineer Association (MCEA) was established in 1991 to promote and perpetuate current and retired Marine Corps engineers and additionally to sponsor and promote an accurate record of their achievements. Fundraising was carried out over a four-year period and was sponsored by the generous donations of caring individuals and organizations, including the Society of American Military Engineers.

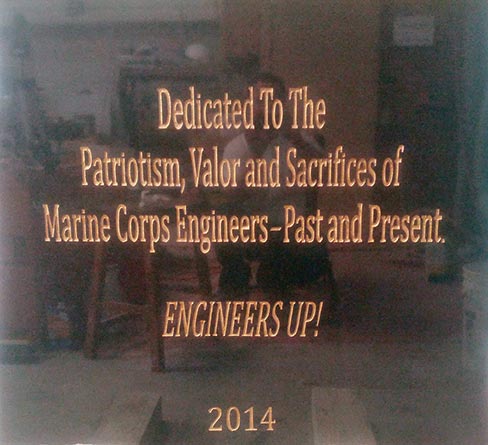

The monument consists of an engraved, five-thousand pound Absolute Black granite pedestal with a bronze medallion (on the back) depicting the Marine Corps symbol, mounted on a base made of Elberton Blue granite. The pedestal, also capped with Elberton Blue granite, holds the symbol of the Marine Corps Engineers: a castle with a half-round cast eagle, a globe, and a rope fouled anchor (EGA) mounted to both front and back. The castle was hand-carved from a single eight-hundred pound block of Elberton Blue granite, and the EGA was made of cast bronze. Additionally, the enclosing hardscape of brick pavers, a retaining wall clad in stone, three-inch thick seating, and landscape were constructed by Stan Cucksee and two William Stone and Tile employees.

The monument consists of an engraved, five-thousand pound Absolute Black granite pedestal with a bronze medallion (on the back) depicting the Marine Corps symbol, mounted on a base made of Elberton Blue granite. The pedestal, also capped with Elberton Blue granite, holds the symbol of the Marine Corps Engineers: a castle with a half-round cast eagle, a globe, and a rope fouled anchor (EGA) mounted to both front and back. The castle was hand-carved from a single eight-hundred pound block of Elberton Blue granite, and the EGA was made of cast bronze. Additionally, the enclosing hardscape of brick pavers, a retaining wall clad in stone, three-inch thick seating, and landscape were constructed by Stan Cucksee and two William Stone and Tile employees.

Making The Maquette

Stan recalls, “I was commissioned by the MCEA in June 2013. Most monument companies use digital imagery to generate their monument designs, but I went a traditional route. I first created a scale drawing and from there built a one-to-one scale clay maquette or 3-D model. Construction of the maquette required over a hundred pounds of clay laid over a wood and wire structure bolted to the ground. This was the model I used to confirm the design with the MCEA. It would have been easier to pull my three dimensional measurements directly from this model by using a pointing device technique to make a one-to-one reproduction, but clay has a tendency to shrink even when kept moist.” Consequently, Stan began recording measurements and performing ‘direct carving.’

“I couldn’t even do a template—I did not have time—yet it was dead on! With most carvings if you make a mistake, it’s called ‘artistic interpretation,’ and that mistake is now a random part of the production process. But with this castle, every dimension had to be exact, making it more than just a carving challenge. It was a geometry problem, and carving was the easy part. The geometry of it, while keeping vertical lines parallel and all the windows lined up, was the hard part. This castle had to look good from two perspectives. For example: you’ve got people walking down a trail full of monuments and the castle is fifteen feet away. It has to look really good when it catches their eye—and also when they walk right up to it, it still has to look good. So it had to look authentic, no matter what distance it was viewed from. Stone is unforgiving, and there are no second chances. If you make a mistake you throw it out and start over. Luckily, it went well, and I only had to carve the castle once.”

Casting The Bronze

With the maquette completed, Stan was able to determine the proportions of the bronze EGA emblems. He then made a model and sent it to a bronze sculptor that he had contracted.

“Mounting the finished bronze work on the castle was like building two parts of the space shuttle in different locations, and then trying to make them fit,” he explained. “The problem with cast bronze, is that they use a lost wax technique, and you can’t get it exact every time. There were slight differences in size and both were slightly warped. Each EGA was in four pieces and cast separately. The anchor itself was in various pieces and had to be welded, ground down and then polished so it looked like a solid piece. The anchor sticks out from the medallion and has a bit of a twist to it. It’s basically a fouled anchor with a rope wrapped around it, which makes it very unique. Even the medallion is a relief, and not a simple medallion.”

Carving And Shaping: A Monumental Task

All raw stone for the project was ordered in block form and shipped to William Tile and Stone, where it was then cut, engraved and finished.

“Compared to carving the castle, which took the longest amount of time, the pedestal and base were straightforward,” explained Stan, adding that only hand tools such as electric grinders and pneumatic tools such as die grinders, air hammers and chisels were used. “It was an eight-hundred pound block, and a ten-inch cube had to be removed between the towers. Thinking back, next time I’ll probably have that wire- sawn out at the quarry to remove it. As far as the rough cuts, they were done at the quarry.”

At the time of shipping, the black pedestal weighed-in at a hefty 5,500 pounds, while the Elberton Blue base and tapered cap weighed a combined 1,600 pounds. Being a master welder, Stan noted that he constructed a custom overhead hoist to help manipulate the pedestal as he engraved it, and additionally, with the assistance of Eric Brown, a retired Marine working at William Stone and Tile, constructed a heavy capacity trailer to transport the monument safely to Virginia.

With the monument now installed Stan drove to Virginia the night before the dedication ceremony to neaten and tidy the area for the following day. He was determined that it would, without fail, be shipshape for the dedication. Leaves had fallen on and around the new monument, and a haze of dust from nearby construction had blanketed the area. Throughout the day, as he was cleaning and polishing, several members of the MCEA walked by, eager to see the monument. Some were exuberant, and some were quietly emotional, but all were pleased to finally have a monument to remember and honor the legacy of the Marine Corps Engineers.

For more information on the National Museum of the Marine Corps go to www.usmcmuseum.org and for information on William Stone and Tile please visit their website www.williamstoneandtile.com.