Tennessee Treasure Julie Warren Conn, Sculptor of Stone

Joel Davis

Special Contributor

Photos courtesy of Julie Conn and Joel Davis

Mouse over photos for captions

The story of sculptor Julie Warren Conn is veined with the same beauty as the stone she loves.

The story of sculptor Julie Warren Conn is veined with the same beauty as the stone she loves.

Veins of history run through her story as well — connections with the past of Knoxville, Tennessee as The Marble City, connections with the Italian artisans who carved Tennessee marble into shapes of dignity and majesty in Washington, D.C. early in the 20th Century.

Veins of history run through her story as well — connections with the past of Knoxville, Tennessee as The Marble City, connections with the Italian artisans who carved Tennessee marble into shapes of dignity and majesty in Washington, D.C. early in the 20th Century.

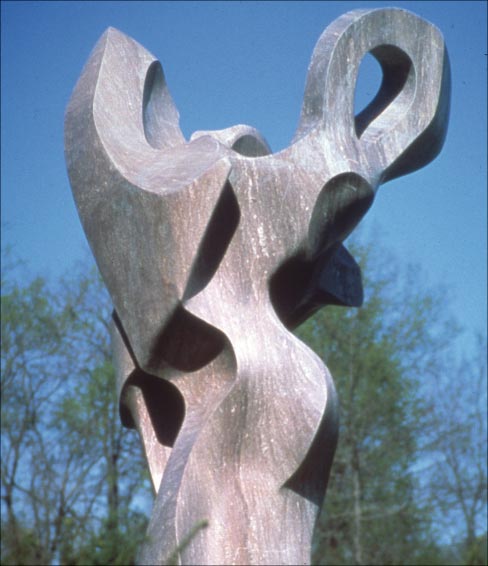

Conn’s work can be described as organic, flowing, refined, and smooth. In her own words, her sculptures range from “form for form’s sake” to abstract, figurative pieces. The extensive use of negative space, opening up the stones, is another hallmark of her style.

Conn’s work can be described as organic, flowing, refined, and smooth. In her own words, her sculptures range from “form for form’s sake” to abstract, figurative pieces. The extensive use of negative space, opening up the stones, is another hallmark of her style.

“My inspiration comes from personal relationships, the wonders of nature, and marvelous sculptures from around the world,” she writes in her artist’s statement. “I admire the entire spectrum of art from the old masters to contemporary artists, as well as many fine ethnic expressions.”

“My inspiration comes from personal relationships, the wonders of nature, and marvelous sculptures from around the world,” she writes in her artist’s statement. “I admire the entire spectrum of art from the old masters to contemporary artists, as well as many fine ethnic expressions.”

Her work ranges from the personal to the massive. In 1990, Conn’s largest work, “Trilogy,” was installed in the Research Triangle Park in North Carolina. Commissioned by Glaxo, Inc, the work includes three statues that weigh 10 tons each.

Her work ranges from the personal to the massive. In 1990, Conn’s largest work, “Trilogy,” was installed in the Research Triangle Park in North Carolina. Commissioned by Glaxo, Inc, the work includes three statues that weigh 10 tons each.

Conn received the first Bachelor of Fine Arts degree with a Concentration in Sculpture bestowed by the University of Tennessee in 1965. Initially, her preferred medium was metal. “I would take flat sheets of hot rolled steel and cut and weld them together to make solid shapes, forming dimensional pieces,” she said.

Conn received the first Bachelor of Fine Arts degree with a Concentration in Sculpture bestowed by the University of Tennessee in 1965. Initially, her preferred medium was metal. “I would take flat sheets of hot rolled steel and cut and weld them together to make solid shapes, forming dimensional pieces,” she said.

Originally, Conn did not believe she’d ever make it as a stone sculptor. Her introduction to the medium had been less than encouraging. “I was given one hammer and one chisel and told to cut the stone,” she said. “That was my instruction!”

Originally, Conn did not believe she’d ever make it as a stone sculptor. Her introduction to the medium had been less than encouraging. “I was given one hammer and one chisel and told to cut the stone,” she said. “That was my instruction!”

The old ways of sculpting by hand, although beautiful, were a barrier to Conn’s entry into the discipline. “Hand pointing is what Michelangelo did,” she said. “In college, I took a hammer and chisel and began chipping away at the stone. I realized early on that there was no way for me to make a living as a stone carver. The process took too long and was extremely tedious. In addition, after a sculpting session my hands were incredibly swollen and sore from the process.”

The old ways of sculpting by hand, although beautiful, were a barrier to Conn’s entry into the discipline. “Hand pointing is what Michelangelo did,” she said. “In college, I took a hammer and chisel and began chipping away at the stone. I realized early on that there was no way for me to make a living as a stone carver. The process took too long and was extremely tedious. In addition, after a sculpting session my hands were incredibly swollen and sore from the process.”

After 10 years as an established sculptor, Conn finally gave stone work another try when a friend, who had been sculpting in Italy, came to Knoxville and offered to complete the unfinished piece from her studies. As he worked, Conn decided to lend a hand and began learning the use of power tools to work the block of Tennessee Coral Rouge marble. It was a revelation.

“When I polished it, I just went crazy. I said, ‘It’s got so much beautiful veining.’ I asked Claude Ledgerwood (owner of the now-defunct Marble Shop in Knoxville, and past MIA President) if I could do another piece. I began working in the mill of the Marble Company. The men working there were showing me how to use electric tools and how to cut. It was a unique experience working in the mill with them.

“There were no women, and there was no one doing the type of work I was doing. They took a special interest and really helped me a great deal.”

With the use of power tools, Conn now faces the reverse of her early trials with sculpting stone — roughing out a piece is the easiest part of the process.

“Now with pneumatic tools, I can quickly cut and break away and shape, but there is a whole lot of sanding involved. It takes me two-to-three times longer to finish a piece as it does to rough cut it. I have become very skilled at rough cutting, but the finishing can really drag out the process.”

The act of sculpting fills Conn with joy. “The way I love to work is just to take a cubic piece of stone and begin cutting,” she said. “I’ll draw some lines on it, and then I’ll do saw cuts and come back with a hammer and chisel. I don’t hand point like the old masters because I would lose the use of my hands.”

Next comes the use of a succession of bushing tools, grinders, and sanders as Conn works to meet her demanding standards for the surface – exceedingly smooth and polished, pleasing to the touch.

“I might use a little bushing tool, a mini-jackhammer, to begin cutting away some areas,” she said. “I start with a large 7-inch diamond blade on my twenty-five pound air saw. I also use a small Makita grinder with a diamond blade for cutting and grinding. I can do a lot of shaping with that.”

Among the tools in Conn’s toolkit: Ingersoll Rand pneumatic saws, grinders, and sanders; a Makita angle grinder; Spiral Cut grinding discs; diamond saw blades, a Dynabrade Dynafile; silicon carbide sand papers, and diamond pads.

“The polishing process starts with an 80-grit grinding disc on an orbital sander, and then I work my way up,” she said. “On some pieces I go up as high as 2,000-3,000 grit. A lot of it becomes hand work, using grit to groove out pieces, and sandpaper.”

The simplest tools that Conn uses are imbued with history, the legacy of craftsmen who worked on some of the most visible and beautiful public projects in the nation — carving the Tennessee marble and other stone used in the construction of federal buildings and memorials in Washington, D.C.

“I was privileged to meet and learn from some of the old stone carvers,” she said.

“They were men of Italian heritage who had come to this country to work on many of the buildings in Washington, D.C. They worked through Candoro Marble and the Gray Knox Marble Companies.

“When I met these men they were in their 70s and 80s, and I would spend hours talking to them,” she said. “They were the true stone carvers working as Michelangelo did centuries before them. They were doing their craft with simple hammers and chisels.”

The relationships enriched Conn. “Some of them even gave me their tools,” she said. “Some sold me their tools. They’ve all passed away now. They weren’t used to seeing a female doing the type of work they had spent their lives doing. It was unique for them, and a fabulous experience for me.”

Sculpting is a passion for Conn, and she delights in stone itself. “Of the Tennessee stones, the Coral Rouge is my favorite and it is probably what became sort of symbolic of me. It was no longer quarried by the time I began focusing on stone, making it harder to find.”

Each type of stone has its own personality, Conn said. “Some stones will even have their own odor. Tennessee black marble is very sulfuric. It has a very unpleasant odor, and, of course, it emits a haze of black dust in the studio as it is being worked.”

Conn worked closely with the now-closed Candoro Marble Company to acquire stone for her sculpting. “I became acquainted with the owners and whenever they would have cubic blocks leftover from larger projects, they would give me a call to see if I was interested in them. Through the years, I got to know many of the marble companies.

“When stone carvers would come to the area from other parts of the country to buy Tennessee marble, the quarries would tell them about me and they would end up on my doorstep. Friendships were formed and we spent hours sharing ideas about working with stone. It was a really neat experience.”

This passion for stone led Conn to some unorthodox methods of acquiring stock. Blasting during interstate construction meant stone for the taking. “Friends and I would go on marble hunts and literally pull rocks off the roadside,” she said.

By the time that Conn left Knoxville in the early 2000s, she had amassed a huge supply. Even after selling off stock in preparation for moving to Oregon, she ended up hauling 50,000 pounds of stone across country.

Conn’s favorite Italian marble is Botticino. “That is a cream-colored stone,” she said. “I gathered up a lot of the pieces from Candoro Marble. Anything I made from it would sell immediately. I haven’t stocked any of that in a long time.”

These days, it is hard to find cubic stone to work, Conn said. She also enjoys working with Colorado white marble and exploring different stones.

“This past year, I began sculpting Kentucky limestone. I had several pieces in my latest show. One is an abstract horse entitled Hot Brown,” she said. “It’s a beautiful, taupe-colored stone. It is very, very hard to sculpt. It is not soft as Minnesota or Indiana limestones. It comes from the Kentucky River palisades.

Normally, it is used for landscaping materials and building supplies. I’ve not seen it used for sculpting. I am constantly searching for new varieties of stone.”

Worries about the safety of her first large piece during installation during the 1982 World’s Fair in Knoxville led Conn to a discovery that changed her approach to sculpting. The 6,000-pound sculpture, called “Terrestrial,” was being lowered on a crane, and Conn was concerned the belt would slip off.

So when she started her next large piece, Conn worked holes through the sculpture to allow belts to be put through the stone, making it secure for lifting.

Soon, the use of empty space became more than utility. “I decided to push the stone as far as I could, which meant I started making larger holes in the rock,” she said. “It was a matter of function when it started, but then I began to explore the negative space as much as the positive space.

“Then it became a matter of making the holes do something other than just being holes through the rock. I tried really to make shapes within the shape, to make it more unique. The more I worked it, the more I pushed it to see how far I could open it up, or see how thin I could make it without breaking,” she said.

Based in Knoxville, Tennessee for decades, Conn now lives in Lexington, Kentucky with her husband, Philip, who retired as president of Western Oregon University. Her studio and showroom are in nearby Winchester. During the winter months, they travel all over the world. For the past 15 years, Conn has taught art classes on cruise ships.

During a 40-year career, Conn has received much critical applause. In 1986, she was named a “Tennessee Treasure” by the state of Tennessee. The first half of her career was documented in “Julie Warren Martin: Sculptor of Stone,” published in 1993.

Unlike some other artists, Conn invites viewers to run their hands across the sculptures. “Sculpture invites you to touch it,” she said. “The smooth surfaces of the stone are especially pleasing.”

The texture of the finished piece is very important to Conn, who spends many hours on sanding and polishing to get it right. “People want to touch stone,” she said. “... I have stone pieces that a person can crawl through as well. It is my intent that the viewer be able to physically interact with my sculpture.”

For more information about Julie Warren Conn’s work, please visit her extensive website www.juliewarrenconn.com.